The Case for Slow Travel on Water

There is a common way to measure trips by how much can fit in.

Cities checked off lists. Landmarks photographed and filed away. The goal becomes coverage. Efficiency. Returning home with proof of having been somewhere even if the feeling of actually being there has already faded.

That approach to travel exhausts in ways that often go unrecognised until it stops. The constant motion. The endless logistics. The nagging sense that whatever is being seen there is something better just around the corner being missed.

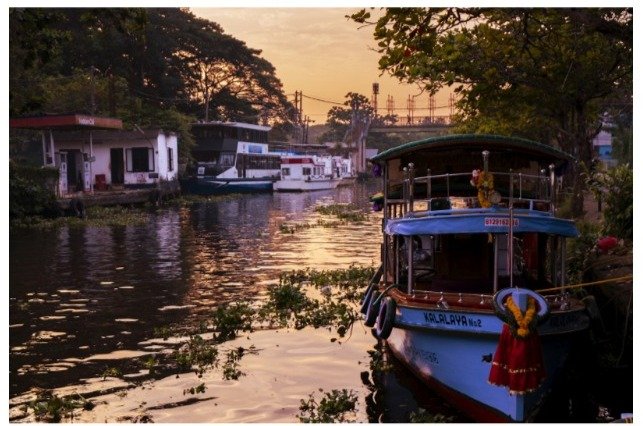

The relationship with travel changes when someone first steps onto a boat.

Not a cruise ship with thousands of passengers and scheduled entertainment. Something smaller. Something that moves slowly enough to actually see what is passing by. The pace itself becomes the point rather than an obstacle to overcome.

Water travel offers something fundamentally different from any other way of moving through the world. The boundaries between transport and destination dissolve. Travellers are not going somewhere. They are somewhere the entire time. The journey is not a necessary evil between departure and arrival. The journey is the whole thing.

Expedition and Wilderness

Some places can only be reached by water.

This simple fact shapes entire regions of the world. Coastlines that have no roads. Rivers that remain the only practical passage through dense wilderness. Islands that exist in splendid isolation from everything land-based travel can access.

Australia's Kimberley region falls into this category. The northwest coast is so remote and so rugged that overland access ranges from difficult to impossible. The landscape is ancient in ways that make most places feel newly born. Gorges carved over billions of years. Rock art that predates most human civilisation. Waterfalls that tumble directly into the sea.

The photographs seem almost unreal. Horizontal waterfalls created by massive tidal movements. Rust-red cliffs rising from turquoise water. A coastline that stretches for hundreds of kilometres with virtually no human development.

Those who make the trip understand why serious travellers consider it among the most remarkable places on earth. The scale is difficult to convey. Everything is bigger and older and more dramatic than photographs suggest.

Accessing this landscape requires the right vessel. When researching options many find that the best luxury cruise operators Kimberley region has to offer run small expedition ships rather than conventional cruise vessels. The distinction matters. Large ships cannot navigate the shallow waters and narrow passages where the most spectacular sights hide. Small expedition vessels can anchor in protected coves and deploy smaller boats for close exploration.

The experience resembles nothing typically associated with cruising. No formal dinners or stage shows or crowds competing for deck chairs. Instead there are expert guides and zodiac excursions and the constant possibility of encountering something extraordinary around the next headland.

What Slowness Reveals

Moving slowly through a landscape changes how it is perceived.

Driving past something at highway speed registers as a single impression. A blur of colour and shape that the mind compresses into a memory of having seen it. The experience lasts seconds even if the landscape extends for miles.

Travelling by water slows everything down. A coastline that would pass in minutes by car unfolds over hours by boat. The same cliffs appear from multiple angles as the vessel traces its course. Details emerge that speed would have obscured. The way light changes on rock faces throughout the day. The birds that nest in specific formations. The subtle variations in colour that reveal geological history.

This slowness requires patience that modern life does not cultivate. People are trained to optimise. To minimize transit time. To treat the space between destinations as dead time to be endured rather than experienced.

Water travel inverts this logic. The transit becomes primary. The destinations become punctuation marks in a longer continuous experience. The rush toward the next thing stops because travellers realise they are already in the thing itself.

This shift in perception proves challenging initially. The mind keeps wanting to hurry. To arrive somewhere. To accomplish something concrete that can be measured and recorded. The boat's pace refuses to accommodate this impatience. Eventually the mind adjusts to match.

Rivers and Their Particular Magic

Coastal expedition travel offers one kind of water experience. River travel offers something quite different.

Rivers move through landscapes rather than along their edges. They penetrate into the heart of regions. They connect places that might otherwise remain isolated from each other. Historically they served as highways before highways existed.

There is something uniquely peaceful about being on a river. The water flows in one direction carrying vessels along with it or requiring work against it. The banks create a contained world. A corridor of experience bounded on both sides by land that is close enough to observe in detail.

Australian rivers have their own distinct character. Murray in particular winds through a country that feels timeless. Red gum forests. Birdlife in staggering variety. Towns that developed as river ports and still carry traces of that history.

River travel often gets discovered almost by accident. Someone suggested trying houseboat hire Echuca for a long weekend. Expectations remain modest. A pleasant diversion perhaps. What often follows is an experience that fundamentally shifts how people think about travel.

The pace proves even slower than coastal cruising. Movement happens at walking speed or anchoring occurs completely. Meals happen when hunger arrives rather than when a schedule demands. Sleep comes easily in the gentle motion of water. The usual boundaries between activities dissolve.

What strikes most is how conversation changes on the water. Without the usual distractions and obligations people talk differently. Deeper. More honestly. The contained space creates intimacy that scattered land-based travel rarely achieves.

The Company You Keep

Water travel is inherently social in ways that other travel is not.

Road trips allow retreat to individual vehicles. Flying means sitting in isolated seats with headphones blocking out fellow passengers. The modern travel infrastructure is designed to minimise human contact while maximising efficiency.

Boats work differently. The space is shared. The experiences are collective. People eat with the same companions repeatedly. They watch the same sunsets from the same decks. The proximity either creates friction or creates connection. Usually both.

Friendships form on boats that would never form on land. The intensity of shared experience accelerates relationships. People reveal themselves more quickly when the usual social scaffolding is absent. The pretences that work in ordinary contexts become difficult to maintain.

This social dimension is part of why many return to water travel repeatedly. Not because more friends are needed. But because the quality of human connection in these settings reminds people what connection can actually feel like when circumstances allow it to flourish.

What We Are Really Seeking

Behind the logistics of any trip lies a simpler question.

What do people actually want from travel? The answers vary by person and by season of life. Sometimes stimulation is wanted. Sometimes I rest. Sometimes challenge. Sometimes surrender to something larger.

Water travel satisfies the last of these desires better than almost anything else. The element itself requires surrender. Water cannot be controlled. It can only be navigated. Travellers can only respond to its conditions and work within its constraints.

This surrender feels like relief rather than deprivation. The illusion of total control that land-based life encourages becomes exhausting to maintain. Water reminds people that they are small. That they are part of larger systems. Those plans are always provisional and subject to forces beyond individual direction.

These experiences deserve continued pursuit. The expedition to remote coastlines. The slow drift down ancient rivers. The particular quality of attention that water travel cultivates.

The efficiency that once drove travel choices seems less important with perspective. What matters is presence. What matters is connection. What matters is moving slowly enough to actually experience what is passing by rather than simply adding another destination to a list.

Water travel offers all of this. It just requires slowing down enough to receive it.